The right way to synchronise event and tracking data

Check out sync.soccer, an open source implementation of my algorithm developed jointly with Allan Clark.

Let us begin by stating what this post is not about: inaccuracies in any particular football dataset. All data incorporates measurement error. For football event data, collected manually by clicking over match footage, this means a degree of inaccuracy when recording event location. The timing of events can also be slightly off due to the collector’s reaction time and perhaps also broadcast delay (if collected live). For these reasons, event data providers invest significant resources in the development of quality assurance processes. But positional data collected by optical tracking of players is not free of error either – these measurements have a fixed resolution, and like with every automated system, glitches happen. If you are interested in discrepancies between event and tracking data, you will be better served by Joe Mulberry’s investigation.

What this post is about:

a method to synchronise event and tracking data (near-)optimally in spite of error. As we move into the next decade of football analytics, combining tracking and event data becomes a must. Tracking data on its own is too unstructured to answer quickly all questions of interest, while event data contains no off-the-ball information. But even if you are one of the lucky few with both sets of data at your disposal and you merge them in the obvious way – by their (implied) timestamps – a typical result is something like this:

Event location inaccuracies aside, we see that matching by time can give a false picture of what goes on off the ball when the event happens. In a rapid play such as this counterattack by the blue team, one second (the resolution of the event data used here) is a lot of time, with players covering a lot of ground. If we used tracking data to annotate events with additional off-the-ball features such as passing options, deriving them from the wrong snapshot may skew the results of any downstream analyses. Perhaps for this reason, event data tends to be also timestamped with sub-second precision, but in practice these timestamps are not sufficiently accurate either (left as an exercise for the reader.) Clearly we need to do better.

There…

For a general solution I turned to bioinformatics. In 1970, Saul Needleman and Christian Wunsch developed an algorithm to match (or align) two amino-acid sequences. Optimality was defined as the smallest number of mutations that transform one sequence into the other. Such optimal alignment represents the most parsimonious scenario of the evolutionary divergence of the sequences, and by extension of the organisms that they came from. Mutations can be “point mutations” (changes of a single DNA letter or amino-acid code) or “indels”: segments that were either inserted into one sequence or deleted from the other post-divergence. The algorithm generalises easily to the case where some mutations are seen as more costly (or less likely) than others – for example a point mutation can be deemed more likely than an insertion of a long novel sequence.

The amazing property of the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm is that it can evaluate efficiently every possible alignment. The starting point is the trivial problem of how to align the first letters of the given sequences: if they are the same, it is obviously the perfect alignment; if they are not, it’s either a point mutation or an indel, whichever the user’s scoring rules prefer. Let’s say it’s a point mutation. Then another pair of letters is added, and we are faced with the task of aligning two sequences of length 2: if the new letters also don’t match we could declare another point mutation, but perhaps now an indel covering both letters is the preferred option – and so on, with more and more letters added until all have been considered and the optimal alignment found. The efficiency comes from memoising at every step the scores of all options under consideration, so that none have to be recomputed to make the decision about the next pair of letters. Under the hood, this is done by constructing a giant array of numbers, each representing the score of an optimal alignment of subsequences.

…and back again

You may already see how the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm can be repurposed for synchronising football data, but let’s spell it out. Our “sequences” are events on one hand and tracking snapshots on the other, in the order in which they are supplied by their respective providers. We want to match every event to a snaphsot, but a great majority of snapshots do not correspond to any events. The algorithm must therefore penalise “indels” where events are “inserted” (i.e. left unmatched) very harshly, but treat the opposite as routine. Events and snapshots are different things and no “point mutations” transform one into the other. But it is possible – in fact, easy – to put a number on the plausibility of a given snapshot representing the instant in which a given event took place. The farther apart the recorded event location is from the location of the ball in the snapshot, the worse the compatibility, and analogously for the event and frame timestamps. For in-play, on-the-ball events, the player identified as performing the event must be very close to the ball in the snapshot for a match to make sense. More quantitative conditions like these can be derived and combined into a single measure of event-snapshot compatibility, but in fact the N-W algorithm built on just the indel logic and the three conditions above yields a huge improvement over naive matching:

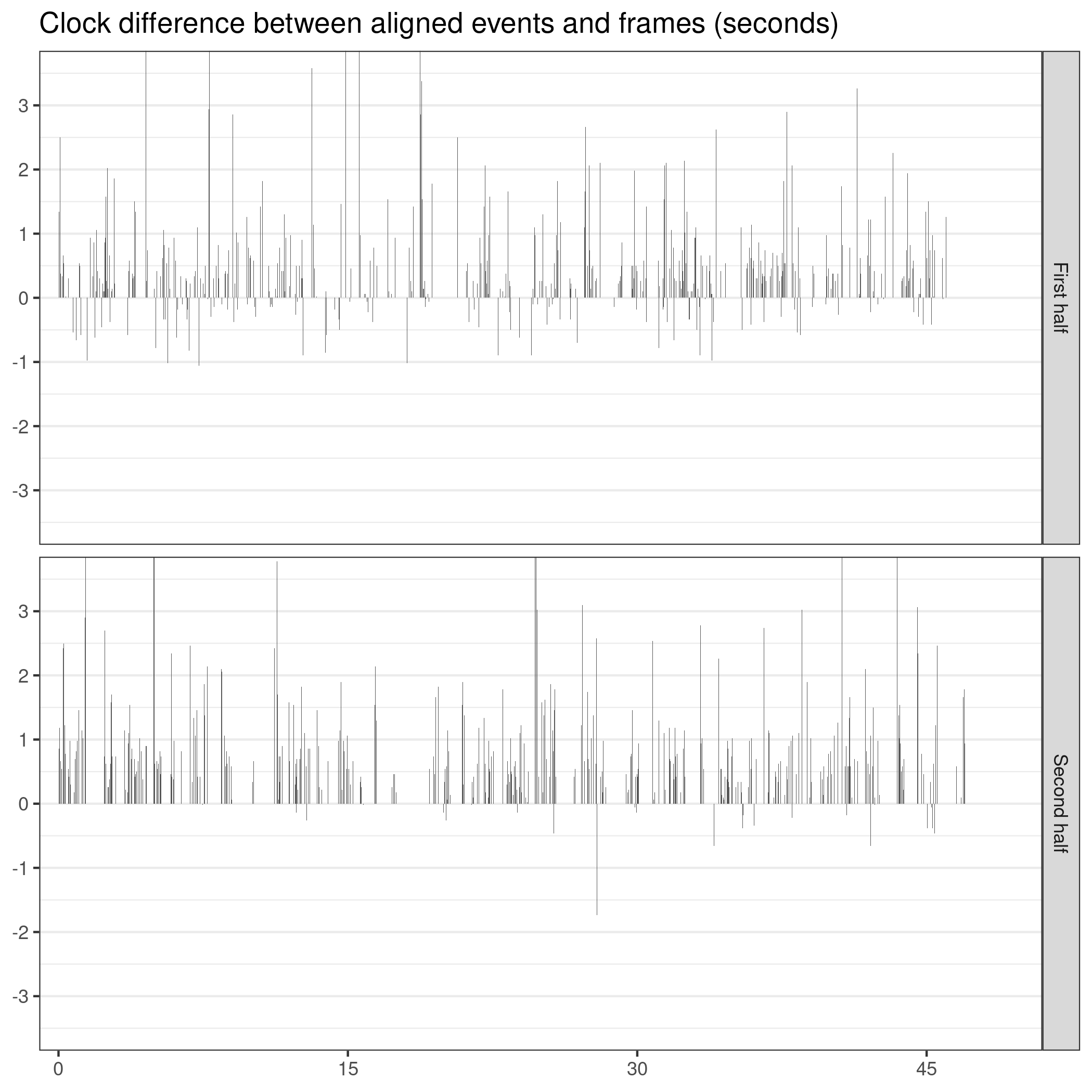

To illustrate the output of the algorithm over the whole game, I plotted the differences between the times of the aligned events (as above, understood as the middle of the appropriate 1 second interval) and snapshots:

The plot reveals that the algorithm is willing to align events to snapshots that are quite far apart in time. Again, this is not to say that the algorithm is absolutely right and the discrepancies necessarily represent errors (at the very least, differences of less than 1 second are completely fine given the resolution of the event clock.) Even comparing the two clips above, while the algorithm does an unquestionably better job overall, at least one event (the final pass) is matched better by the naive method. But what the plot does show is that the algorithm offers a candidate alignment different enough from the naive one to have consequences for downstream analyses. And if you are wondering about the overall bias towards positive values, meaning that snapshots get matched to events tagged with time that’s slighty “in the future”, so am I. The algorithm has produced this pattern throughout the tiny sample of 12 games of tracking data in my possession, although it is sometimes reversed. It can be due to the algorithm being wrong (although ad-hoc animations do not support this), broadcast delays, collector’s reaction time, or mis-identification of the snapshot corresponding to the kick-off, on which the tracking data clock is based (perhaps the likeliest explanation given the occasional reversal.)

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that while I focussed on synchronising event and tracking data, the method is completely generic and can be also used for synchronising two streams of event data, or two sets of tracking (the latter would be particularly easy since the compatibility can be defined in purely geometrical terms.) If you want to, you can even try matching a data feed to crowd footage based on how noisy it is and how high above their seat the average spectator is. And thanks to the algorithm working incrementally, it is also very well adapted to live applications, by producing the best alignment continually as new snaphots and events come in.

Introducing sync.soccer

Together with my friend Allan Clark, I implemented the synchronisation algorithm and released it today as sync.soccer. It is open source software, written in Haskell and licenced under Affero GPL. If you find it useful, it would be nice if you acknowledged it in your work.